on setting personal goals

“A dream’s only a dream if work don't follow it” -Kendrick Lamar, Institutionalized

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how we set personal goals. I studied social psychology and that’s led to a longstanding curiosity about how we self-actualize: that is, when every other step of Maslow’s hierarchy has been taken care of, how do we become the most fulfilled, best version of ourselves?

I’ve taken for granted that goals are the stepping stones to this best version of ourselves, and this ongoing focus on goals stemmed from this assumption. I spent time on the Google Calendar team researching what people put on their calendars (spoiler alert: it almost never lines up with what they say is most important to them). Later, I co-founded a company that sought to help people live more intentionally by connecting their daily actions — encouraging small habits — with the person they envisioned themselves being.

Goals are of particular interest to me because they’re so deceptively simple: state the goal, work towards it, and if all goes well, you achieve it. But it turns out that despite our best intentions, most of us aren’t particularly good at seeing this through to the end. There’s a multitude of reasons for this, and while we may kick ourselves believing it’s our lack of effort or discipline, there are a few things we can do to establish a system of goals and give ourselves much better odds from the outset. Goals should be:

✅ specific and measurable inputs:

A goal of “getting in shape” is ambiguous: what does that mean? What do I do each day to work towards it? How will I know when I’ve achieved it? Instead, setting a goal of exactly what you’re doing and for how long–“going to the gym 3 days a week for 30 minutes”–is clear, measurable, and specific.

✅ timeboxed:

It should have an end date, so you know what you’re committing to and for how long. BJ Fogg’s work on Tiny Habits is a good primer on this, and don’t be afraid to start small and commit to a shorter time frame — say a month — and then evaluate and see if you want to continue it. Having a timeframe can be a huge help when you feel like quitting – if you know you only have to do a few more days or weeks, sticking it out will be much easier than having no end date in sight. And also, every person and every goal is different, and while the 21-day habit formation theory is often quoted, habit formation can be as long as 8+ months.

✅ tracked:

Whether you use a journal, a Google Sheet, or one of the many apps available, having a place to mark progress helps enforce the habit, keep you on track, and also provides a nice little bit of serotonin when you can look at what you’ve accomplished so far. Create one where you can easily see how you’re pacing, and developing a habit of tracking your habit can provide a boost when you see the impact checking a box for the day translates directly into your pacing towards your goal.

✅ socialized:

Under the right conditions, telling a close friend your goal — the specific, measurable, timeboxed, and tracked version of your goal––can be a great way to be held accountable to it. The catch here is that you/your friend actually follow up, and you are held accountable to that goal. In some cases, socializing a goal, say telling a friend that you’re going to record an album, elicits a positive reaction such that you feel like you’re getting credit for having completed the goal, which actually can just widen the intention-behavior gap and make you less likely to do it. The key I’ve found here is to set up the accountability mechanism at the time of setting the goal so that if I fall off or don’t start, I don’t get to pretend like I never set the goal.

All of these are helpful ways to set goals and help us stick to them, but taking a step back: the purpose of the goal is to become that best version of ourselves. The dilemma most of us face in setting goals traditionally has been we have a vague notion of the end result, but without the specificity of what am I doing today to advance towards that goal, we’re left with inaction.

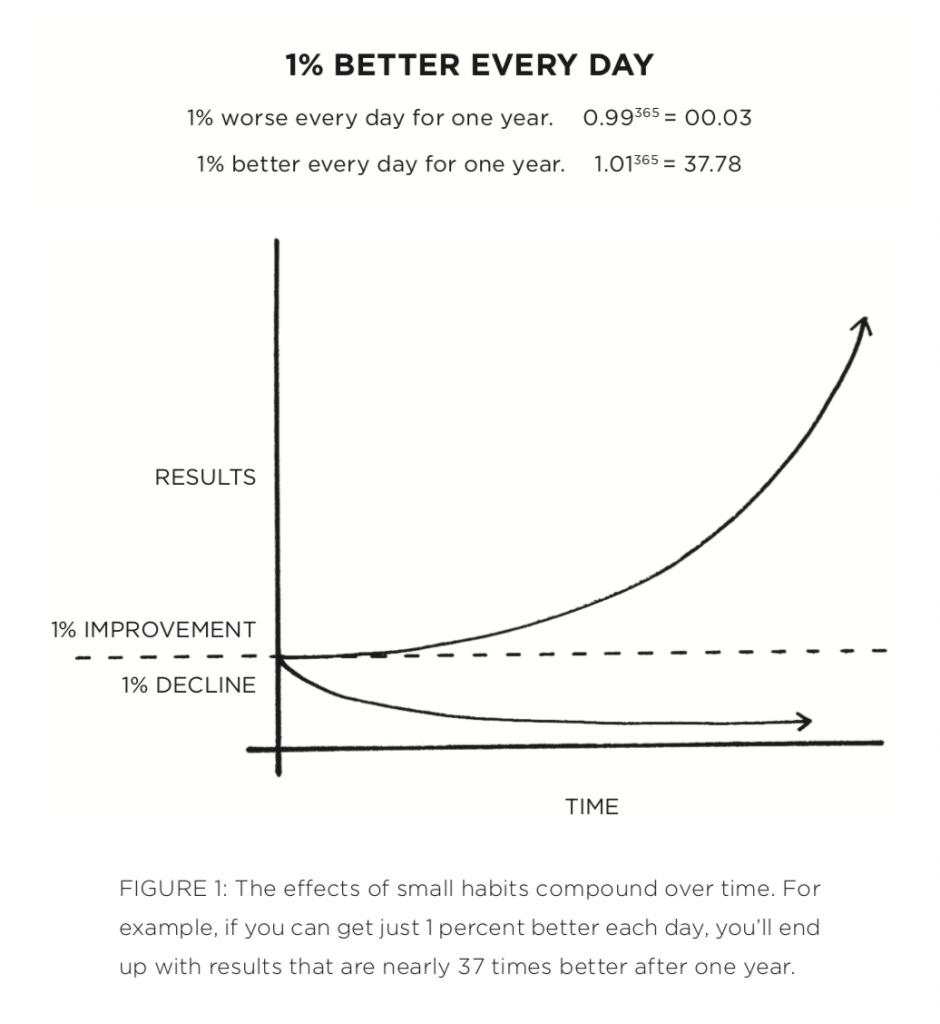

How many times have you heard someone say that they’d like to be fit, or better read, or write a book, and then leave it at that? Creating a goal with the above parameters gives you the benefit of a direct action you can take each day (or week, or whatever) that will compound over time to achieve the goal.

“In life, people emulate the end result & not the process. The end result is what they see and they emulate that. All those free throws - before Kobe scored that 81, that day, he was practicing. He practiced his whole life. Are you willing to put in that sort of commitment? Are you willing to practice your whole life? You know Mayweather, Mayweather’s running right now probably. Yeah, sure you want to be on the jet and all that, but do you want to put in that work? That’s what it takes for something great. That amount of time, that level of commitment.”

-Jay-Z, video

I mentioned I’ve taken for granted that goals must be the stepping stones to connect who you are with who you want to be. I think that’s mostly true, but as with anything, there’s nuance, and an overfocus on the daily routine associated with the goal can lead to losing track of why we set the goal in the first place: becoming the best version of ourselves.

James Clear makes a compelling argument for a focus on systems over goals (his piece is worth a read if you haven’t yet), and I agree: when the steps to achieving a goal become rigid and we lose sight of the end target, we’re much more likely to fail. Reassessing whether the goals you’ve set align with your long-term self-vision ensures that you’re not losing that focus, and tying your action each day to an aspirational identity – what would an athlete do today? what would a writer do today? – and making choices based on that identity can be a great solution for some people.

In any of these, creating a habit is crucial. Whether it’s following the rubric I laid out or if your specific goal is to ask yourself every day what a certain type of person would do, consistency is key. Find ways to put yourself in a position for incremental improvement every day/week/month, and reward yourself along the way by acknowledging progress and being able to see how you’re measuring up to what you said you’d do. Set a timeframe, be specific about what you’ll do each day, track it, and have someone hold you accountable. Otherwise, you’re just hoping to emulate the outcome without setting up a process to get there.